In a warehouse, a forklift truck driven by a newly hired worker spins out of control and crashes, destroying property and injuring a quality control supervisor.

The young driver is near tears, the supervisor overflows with accusations, another worker slips in a pool of oil and injures his head. Everything is confusion.

Eventually when the mess is sorted out, the safety manager will conduct an investigation. He learns that the brakes on the forklift were bad. Someone will get blamed and the brakes will be fixed. The safety manager, overwhelmed by demands on his time, will go off to fight the next fire.

This is not an extreme case. You see accidents handled like this every day. At best, this kind of approach deals with symptoms. In a few days, another piece of equipment, perhaps an overhead crane, will fail. Someone else will be injured and maybe killed. The plant will shut down for a while, the damage will be repaired and insurance costs will be ratcheted up another notch or two. The risks will remain.

To avoid this, an accident investigation must get to root causes. Why was the new employee driving a forklift? How much training had he received? Why wasn't the faulty equipment taken out of service immediately? Why wasn't it clearly tagged? Reported? Were employees fatigued? Stressed? Was it regularly inspected? Is there a preventive maintenance program? What must be changed in maintenance, training or safety to keep this from happening again?

A professional accident investigation should always focus on causes: the why's. Accident investigation should be a critical part of loss control. Done correctly, it can enhance safety and reduce costs. Employers complain that workers' compensation is driving them out of business, but studies show that property damage and downtime resulting from accidents cost companies five to 50 times more than the workers' comp. The highest ratio is in industries with large capital investments, e.g, petrochemicals and heavy manufacturing. Most organizations don't track these costs, which are usually embedded in maintenance budgets.

One of the key objectives management can establish is to ensure that all accidents, including minor property damage incidents and near misses, are investigated. The more incidents that are reported, the more problems can be investigated and resolved. The more problems solved, the safer and more cost effective the operation will be.

The fact is that the only difference between a near miss and a catastrophe may be chance. That's why every potential problem should be resolved. Most organizations don't have the resources to do this.

Supervisors a Critical Resource

Typically, accident investigation is the sole responsibility of the safety manager. But with limited resources, this individual seldom can investigate all incidents that should be investigated. An effective solution is to involve front-line supervisors in the process. This is the best way to ensure that an organization has the resources to investigate all the high-potential incidents that should be examined.

Of course, someone with higher level jurisdiction should ultimately be in charge of the investigation to ensure that best practices are followed and that the results are acted on by the organization as a whole. This might be the job of the safety manager. Ideally, the safety manager should directly conduct investigations only in situations where the loss or potential for loss is severe. Otherwise, the individual should be a resource whose expertise others can draw on.

To meet the goal of making accident investigation a regular part of the management system in organizations, try following this three-phase accident investigation process.

SIDEBAR:

Accident investigation begins with controlling the initial response. When an accident happens, the initial response is crucial not only to minimize injury and loss, but also to protect evidence necessary to conduct the investigation.

To structure the initial response, there are "Seven Steps of Investigation" that enable organizations to proactively respond to incidents while laying the necessary groundwork for Phases 2 and 3 of the accident investigation process.

1. Take control of the accident scene: Accidents make people react differently. They are curious, irrational or confused. They may freeze. A leader -- typically a supervisor -- needs to take charge, and fast.

2. Ensure first aid and call for emergency services: If necessary, the supervisor should give urgently needed first aid and assign someone to keep the injured calm.

3. Control potential secondary accidents: An accident scene can be a trap for those seeking to help. In this environment, the leader needs to spot potential problems and warn others.

4. Identify sources of evidence at the scene: The supervisor needs to identify evidence at the scene because such evidence may be moved or removed during the emergency response or attempts at rescue work.

5. Preserve evidence from alteration or removal: After evidence has been identified, it must be preserved. The supervisor should use employees to block off evidence to keep it from being moved or cleaned up.

6. Investigate to determine the loss potential: The supervisor or leader needs to make a prompt appraisal of how serious the accident could have been and how likely it is to occur again. The individual can then decide how in-depth the investigation should be.

7. Notify appropriate managers: Some managers may need just a courtesy notification. Others may need to be on the scene right away.

Phase 2: Collecting Evidence and Information

When an accident investigation begins, investigators are faced with a puzzle. They have to figure out, first, what the pieces are and, second, how the pieces go together. To do this, they must gather and begin to interpret the evidence. In this process, it's very easy to overlook key pieces of information and thus end up with an inaccurate picture of the event.

A simple method for gathering information structures evidence into four categories. It's called the "Four Ps" for Position, People, Parts and Paper evidence. The four types are listed in order of fragility. Since each type of evidence is different, each must be collected differently.

Position Evidence: This relates to the position of the people, equipment, materials and the rest of the environment that existed when the accident occurred.

It may be the location of an oil slick, an overturned forklift truck, boxes of merchandise that spilled from a pallet, a ladder lying on a warehouse floor, a clipboard carried by a victim, and so on.

Since much of this evidence will be removed or moved during and after the initial response, investigators typically preserve it by drawing sketches or by using a camera to photograph the scene.

People Evidence: Witnesses are the people who know something about what happened. Some are eyewitnesses who saw the accident happen. Others may be people who designed facilities, ordered materials, trained operators and so on. The tool for collecting information from witnesses is the interview.

Memory and willingness to talk can be affected by the interviewer's technique. Here are some basic guidelines to follow to conduct effective interviews:

- Interview witnesses separately so they don't influence each other's memories. Interview them in a place away from the workplace or other distractions.

- Put the witness at ease. A simple inquiry about the person's condition should be sufficient.

- Get the individual's version of what he or she remembers. The investigator should never challenge the story.

- Ask necessary questions at the right time only to prompt more detail.

- Give the witness constant feedback by putting key points into your own words.

- Record critical information by quickly making notes of key points. Avoid using recorders except in special circumstances. They make people uncomfortable.

- Use visual aids -- sketches, photographs, blueprints, models -- when appropriate.

- End on a positive note to keep communication open. Ask for ideas on how to prevent similar incidents.

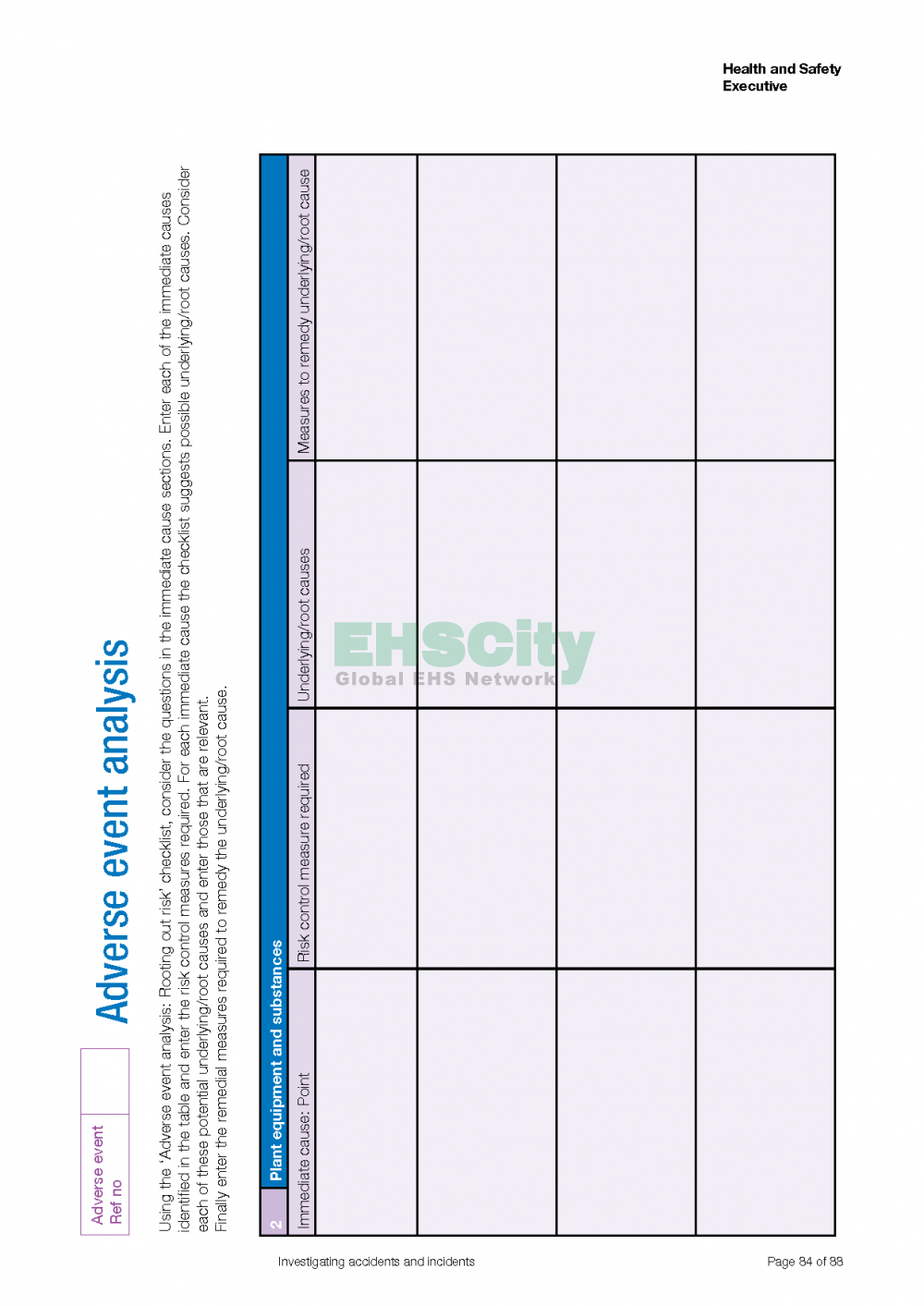

Parts Evidence: This type of information includes a look at the tools, equipment and materials people were using.

Investigators should review standards for usable conditions, for guards, safety features, and hazard warning labels. Investigators should also look for failures in equipment and structures and ensure suspect parts are saved and examined.

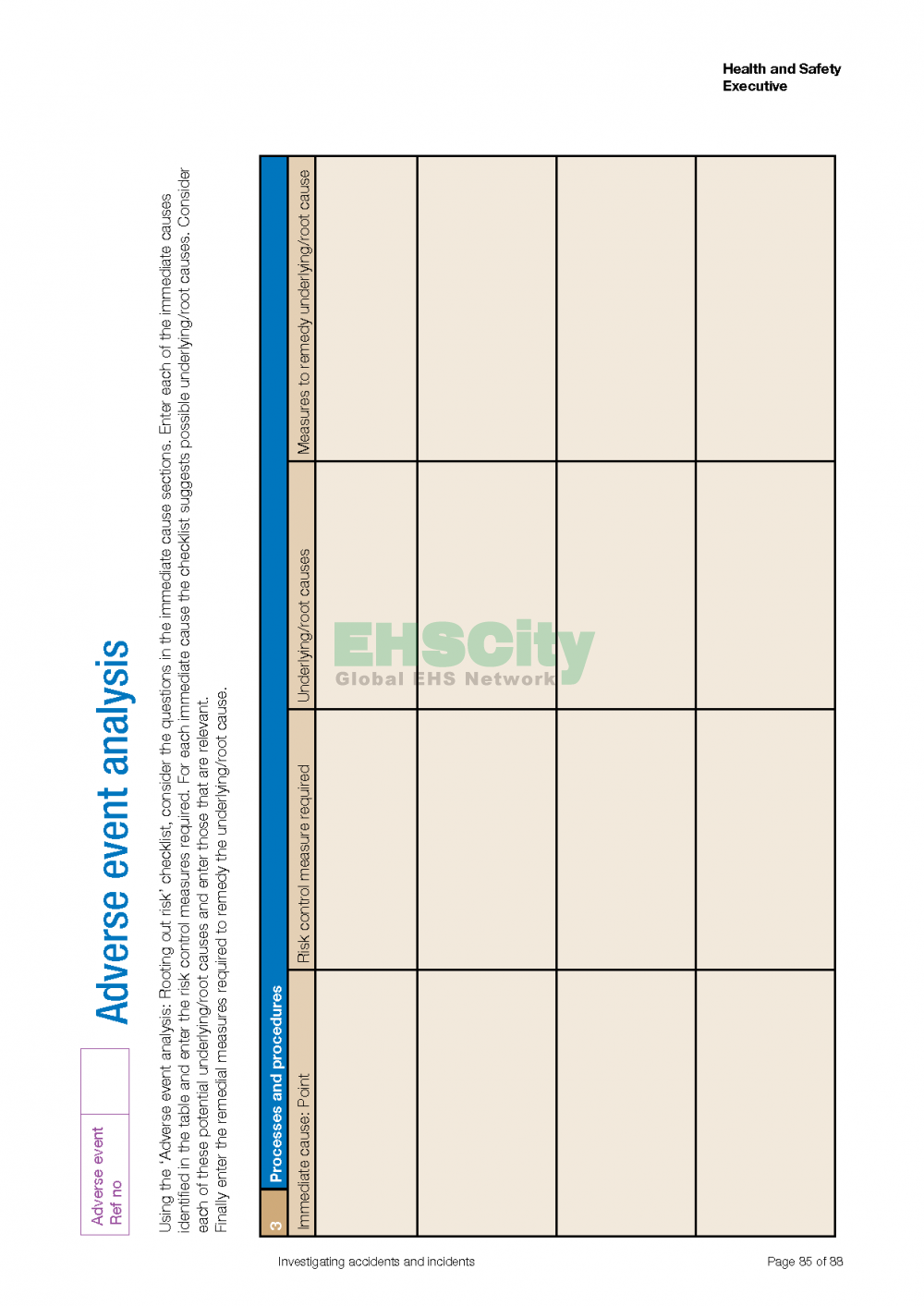

Paper Evidence: In general, position, people and parts evidence, when evaluated, give the investigator a sense of what happened.

By contrast, documentary evidence leads to the underlying or basic causes. documentary evidence is not self-attracting; the investigator has to dig for it. Here are some examples:

- Training records: Should be checked when a person hasn't used the right procedure or equipment.

- Maintenance logs and records: Should be checked when equipment seems worn, previously damaged or in disrepair.

- Schedules: Should be checked if people are trying to operate and service equipment at the same time or if there is evidence of congestion, interference, fatigue or stress.

- Job procedures and practices: Should be checked to ensure there are current standards for the jobs being done.

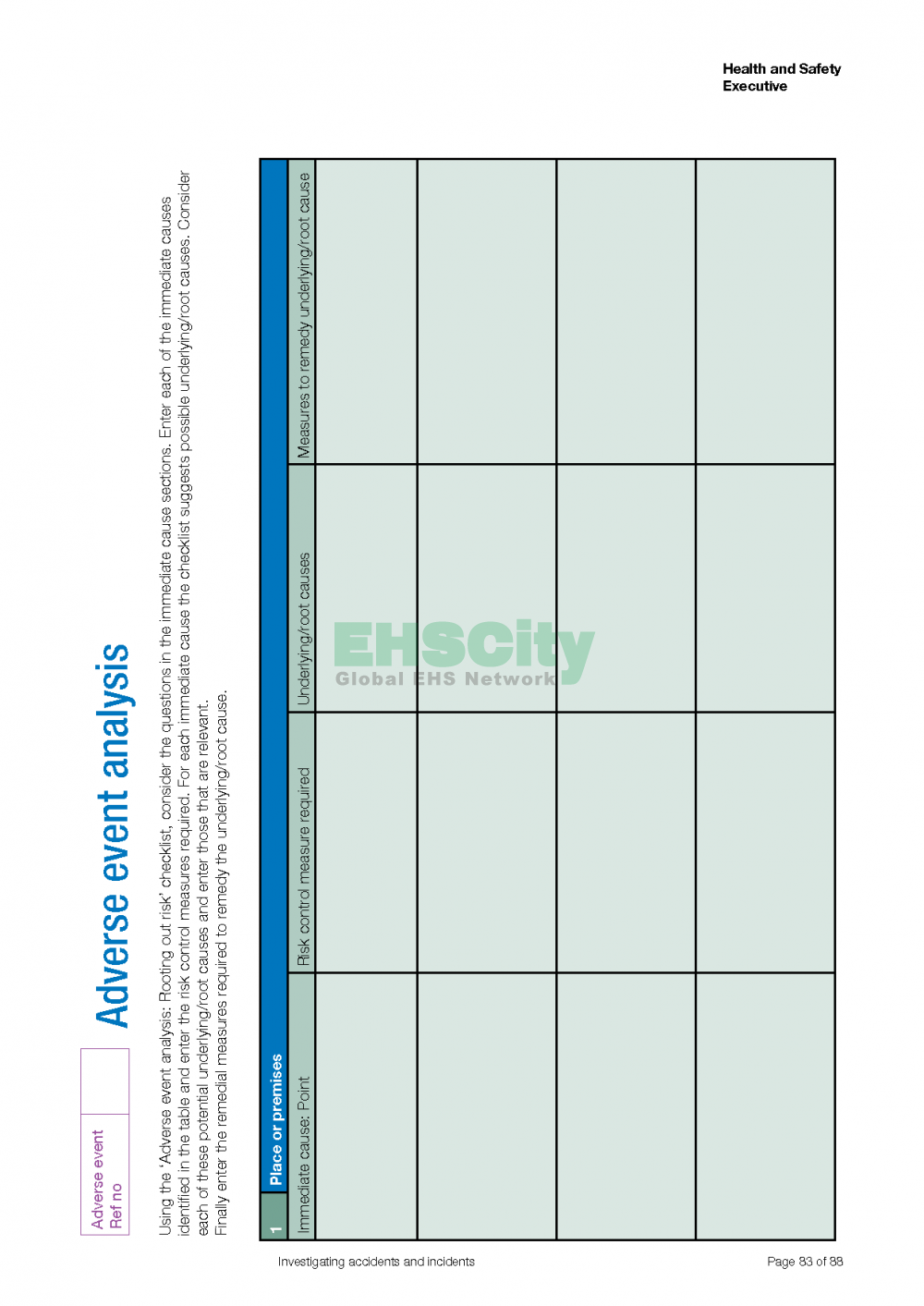

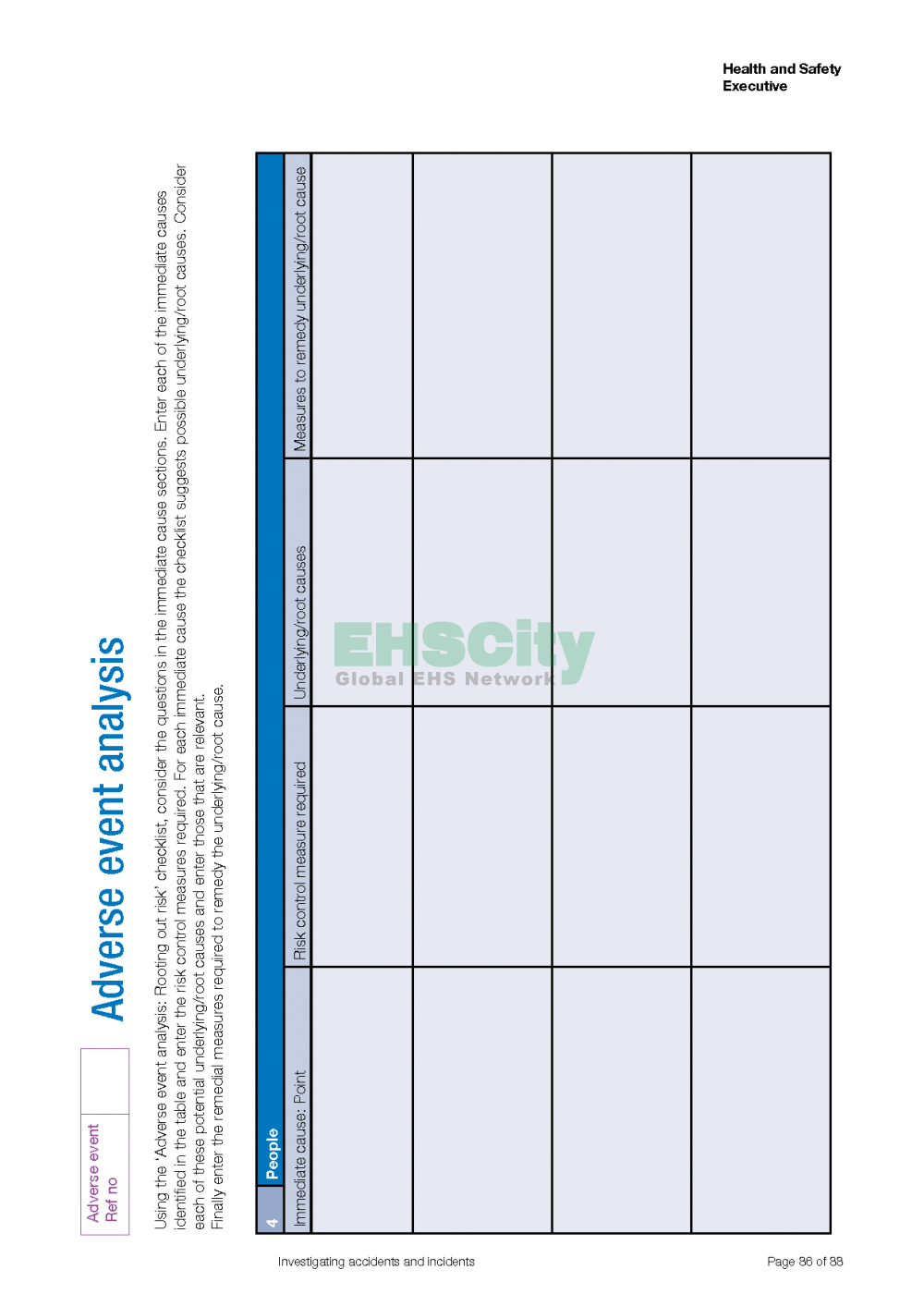

Phase 3: Analysis & Correction

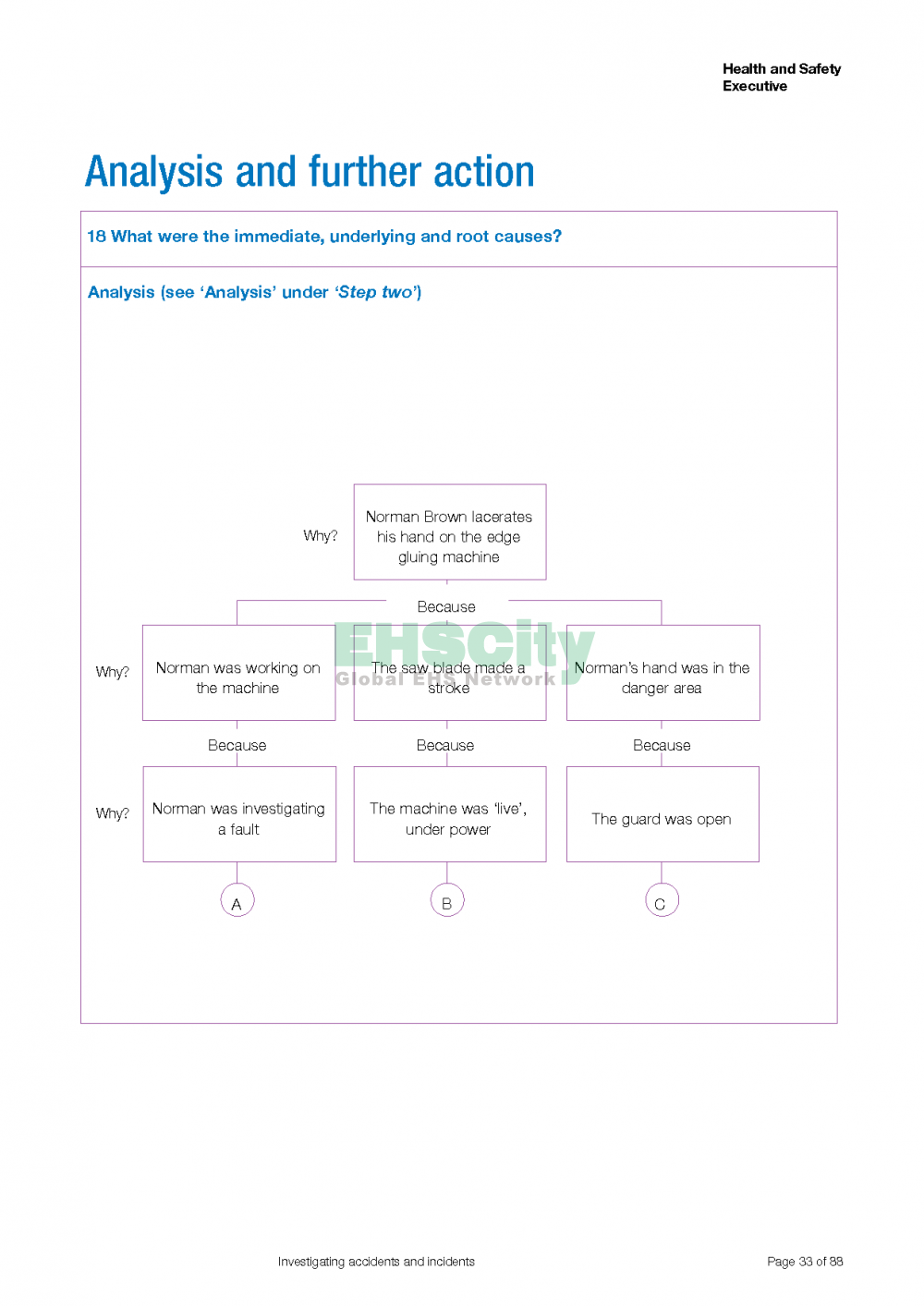

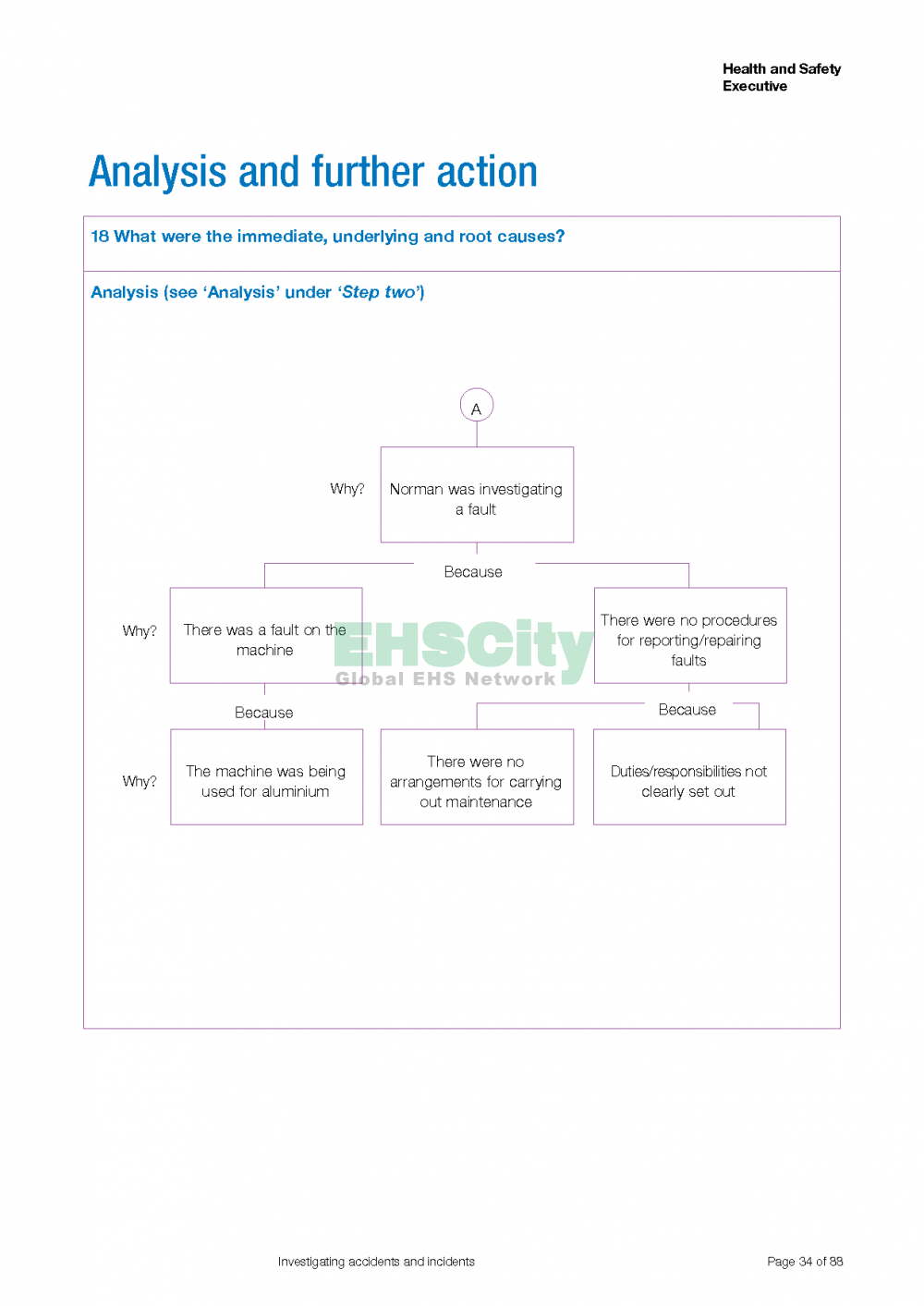

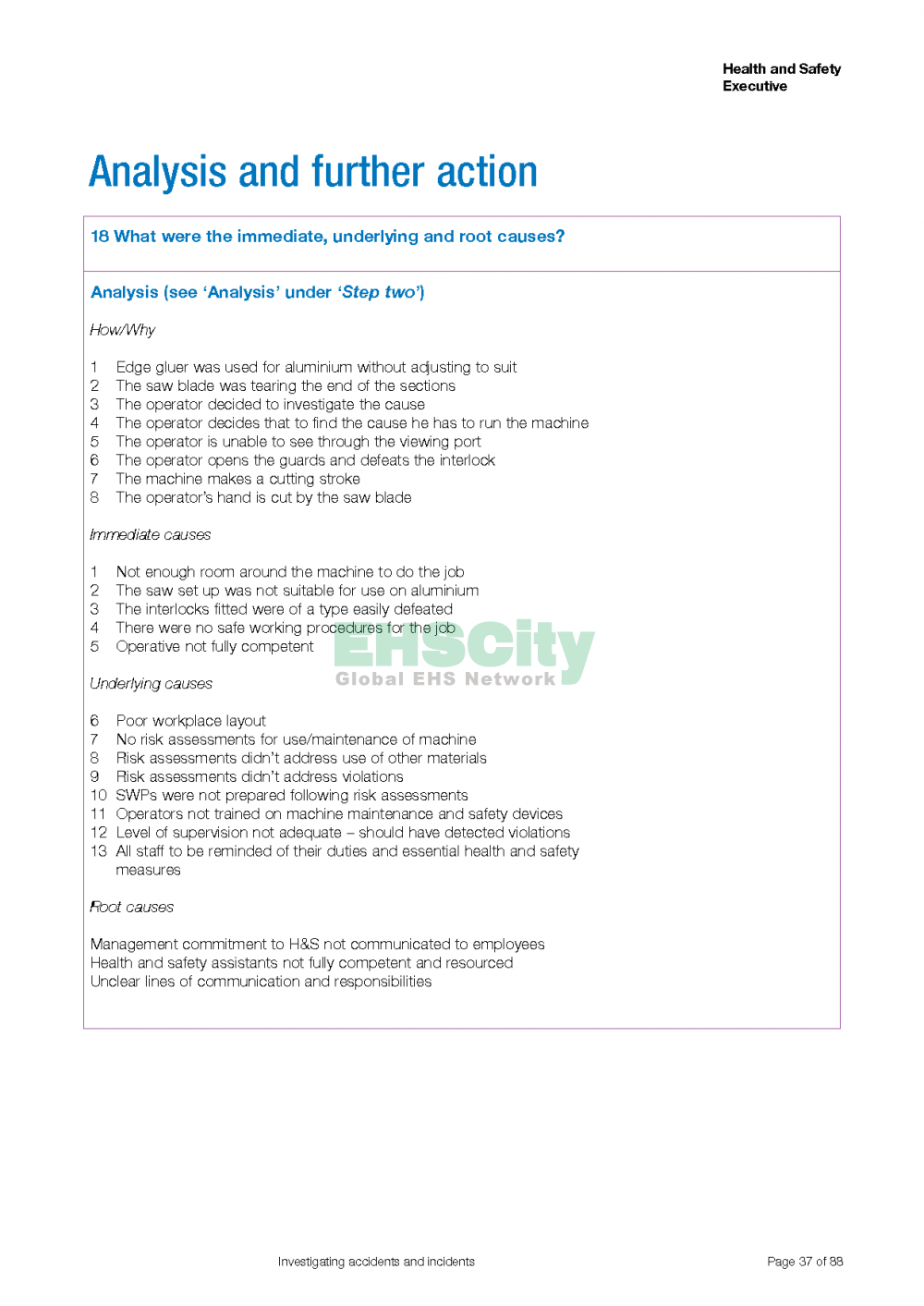

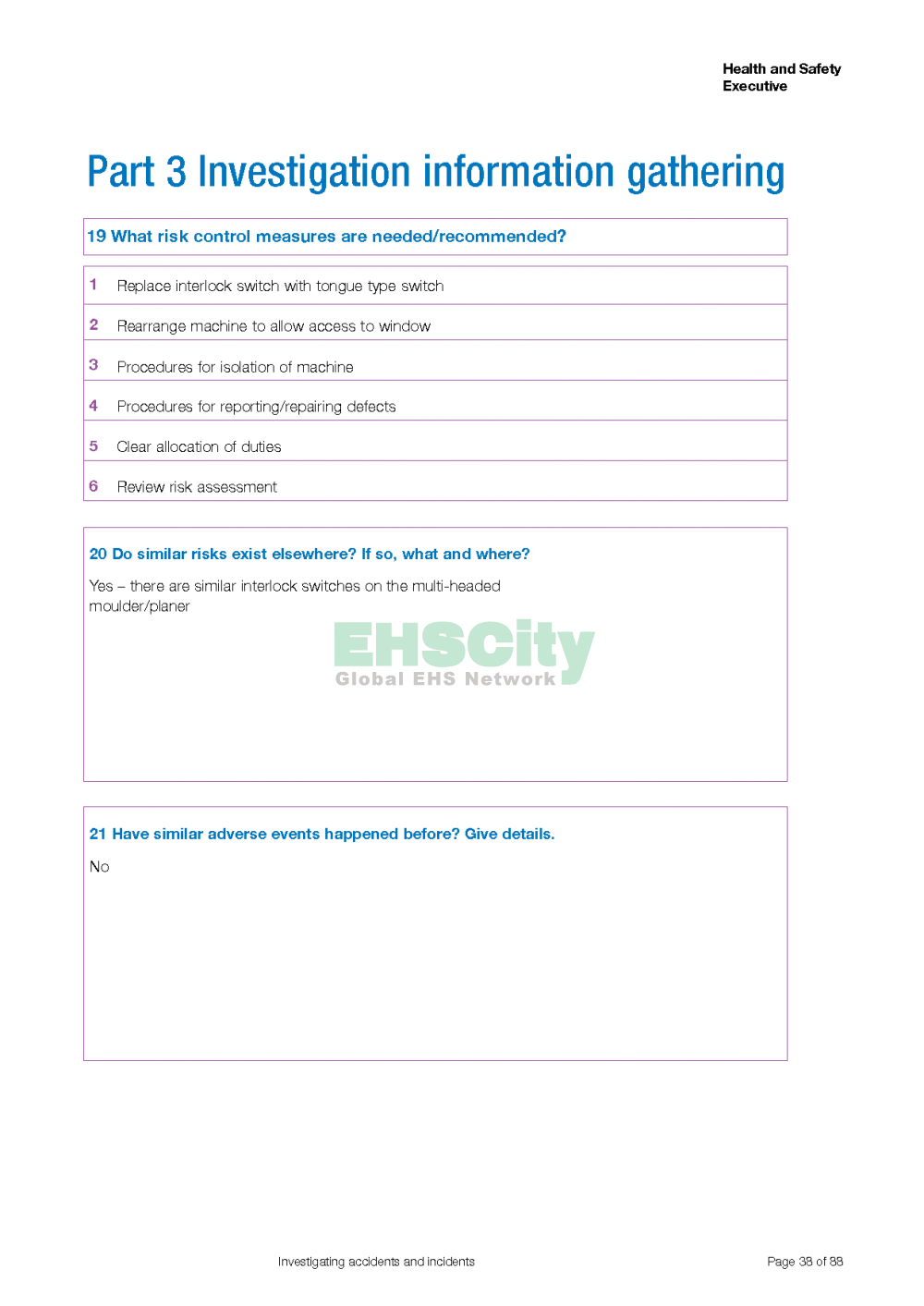

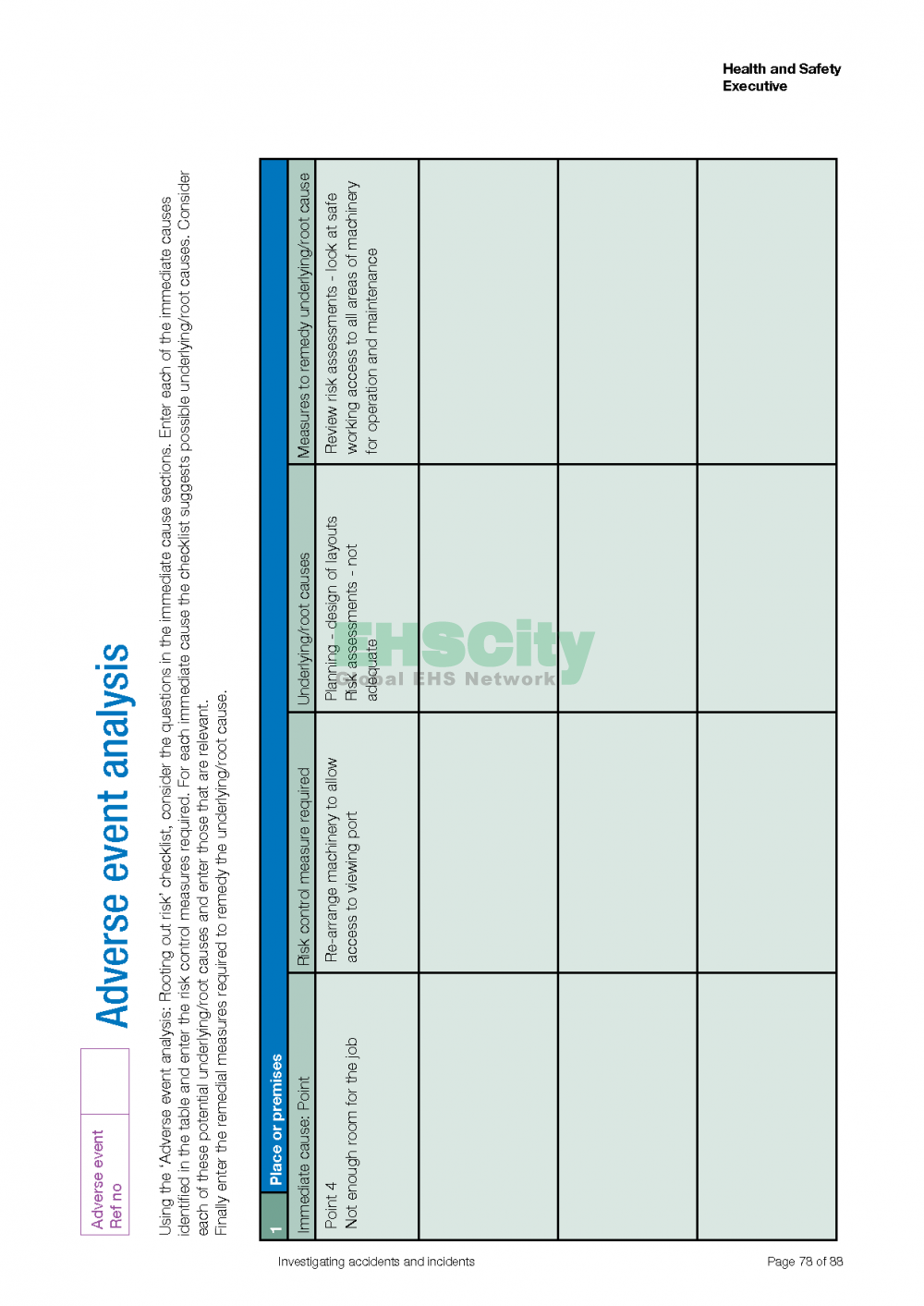

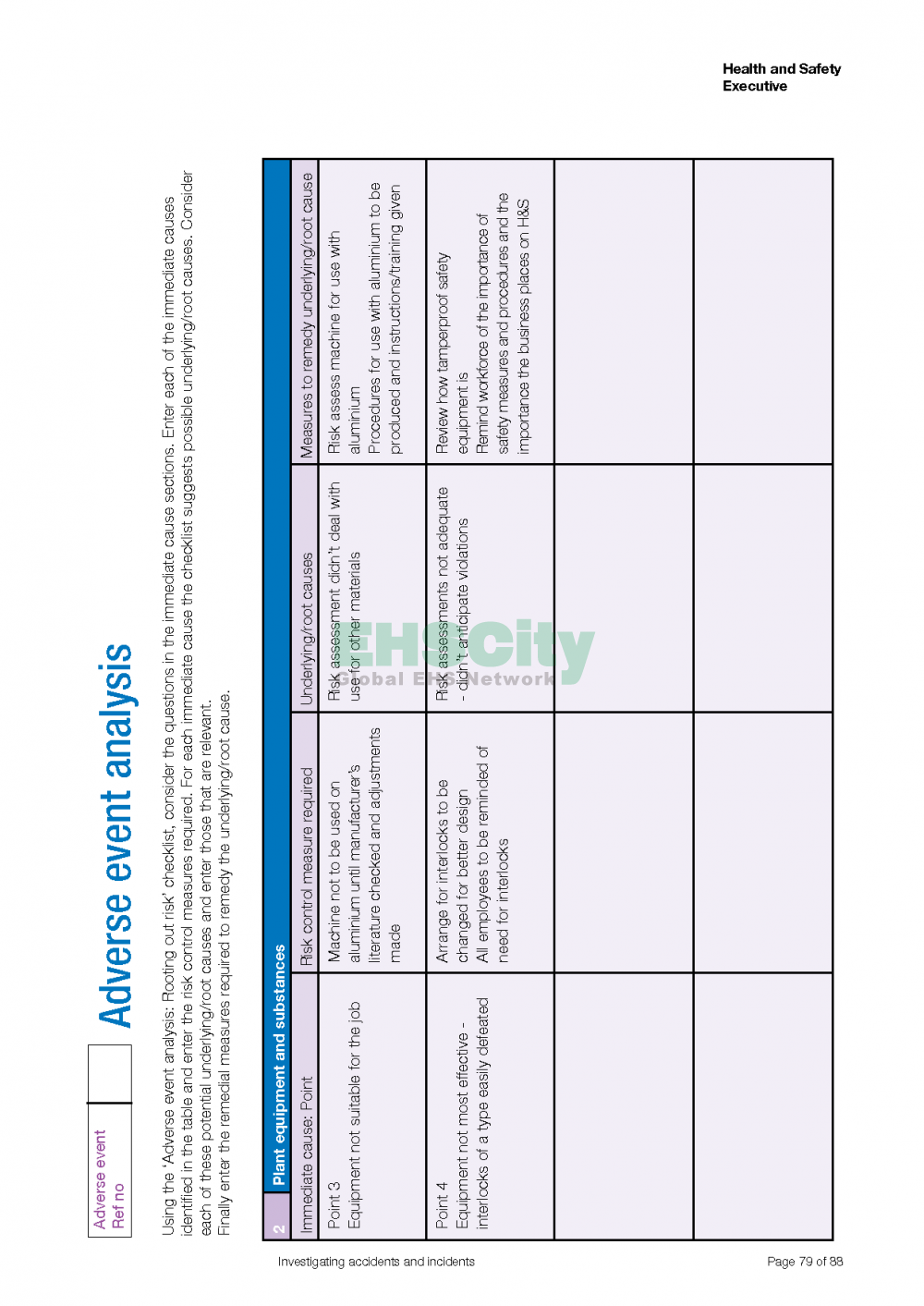

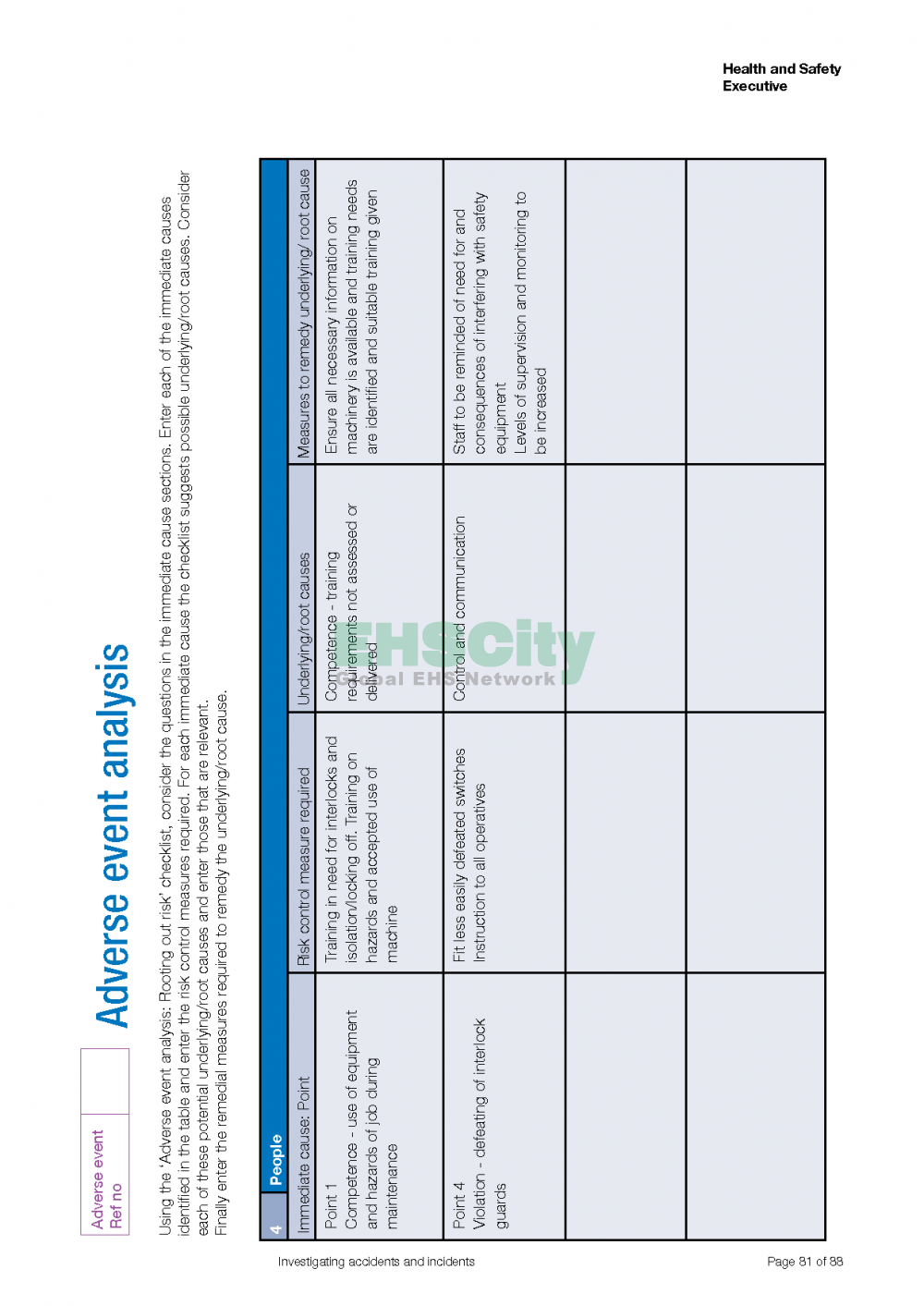

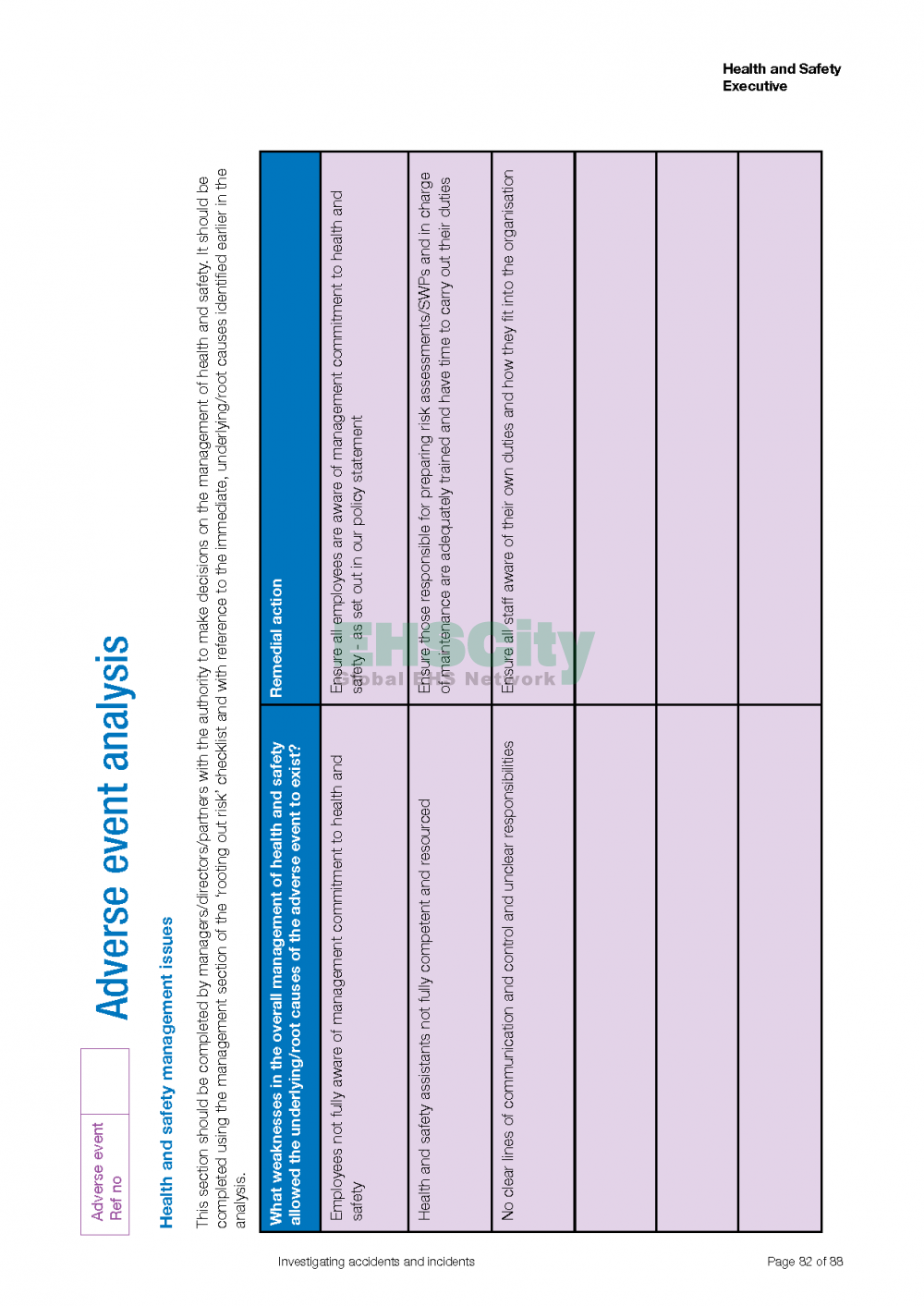

After evidence is collected, the next task is to analyze it to determine causes, identify corrective actions and develop a report for management. The goal is to prevent recurrence of an incident.

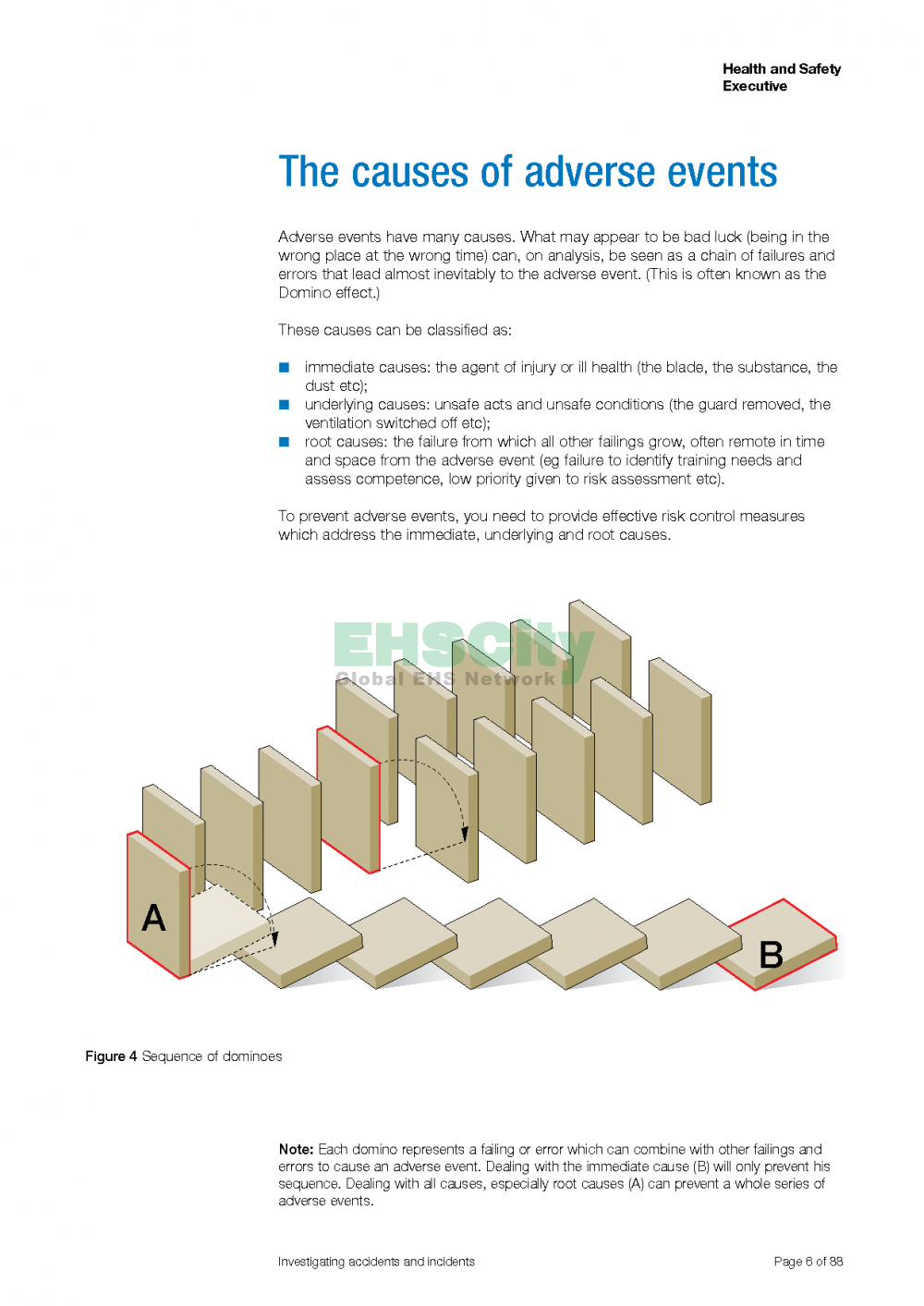

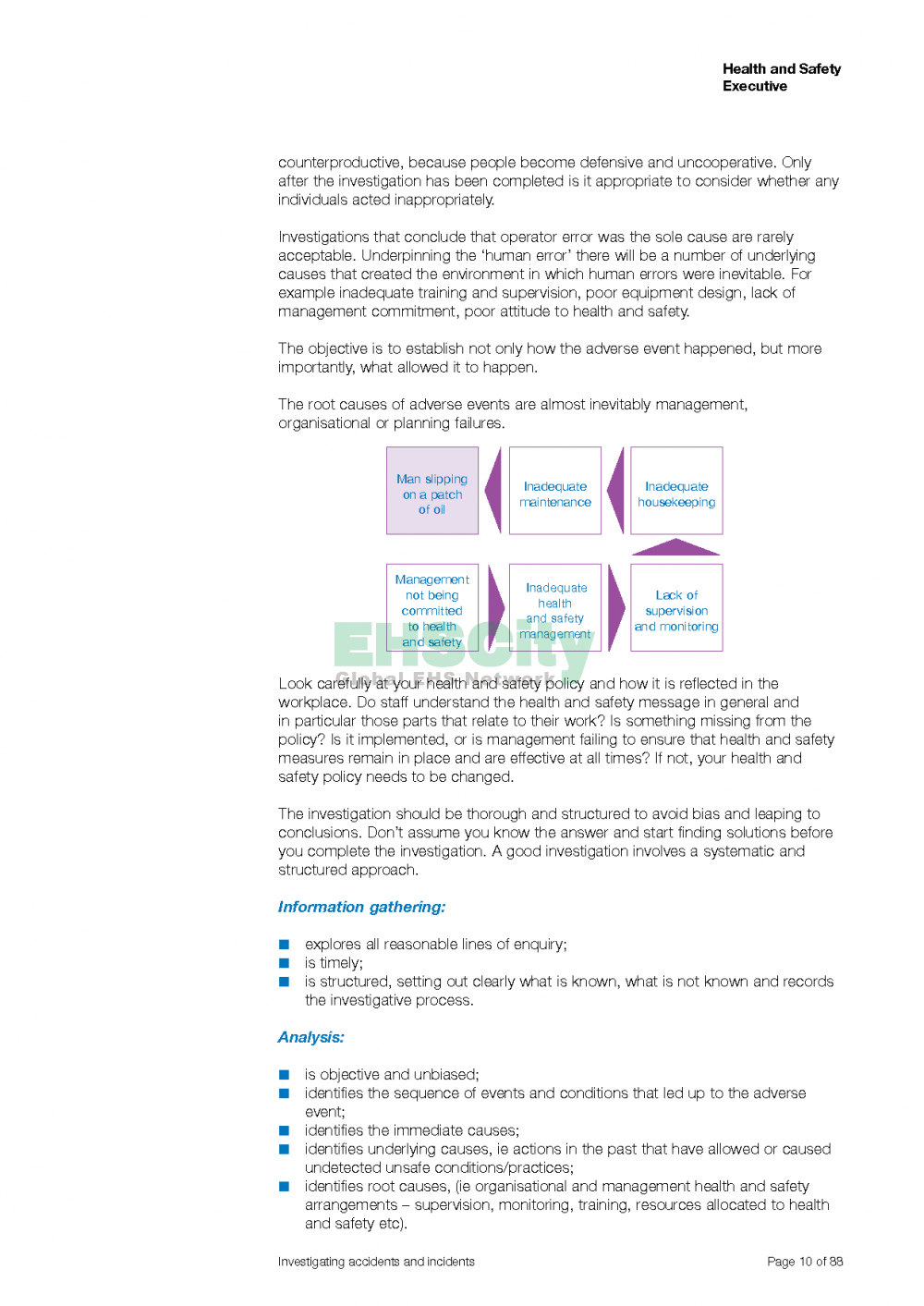

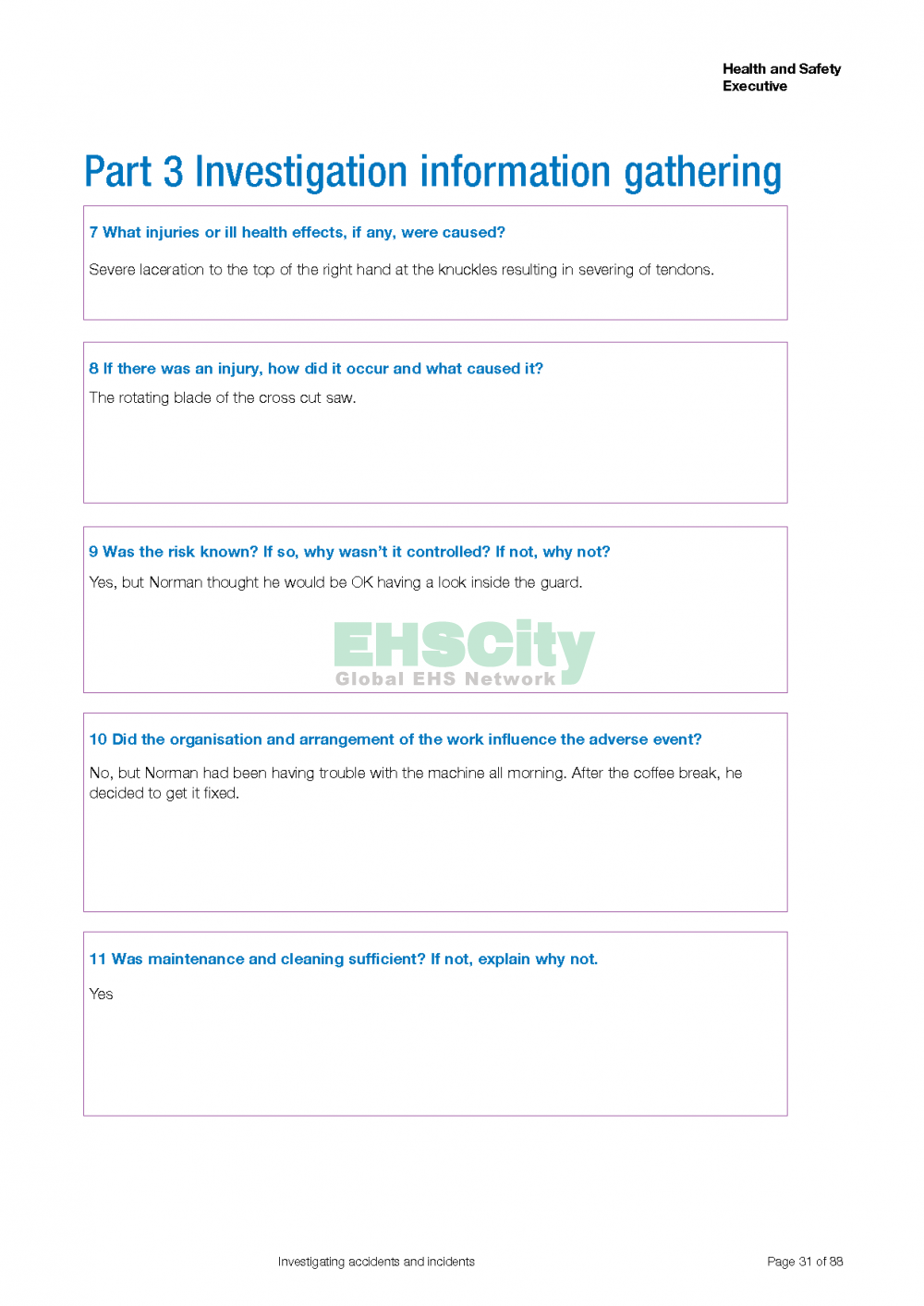

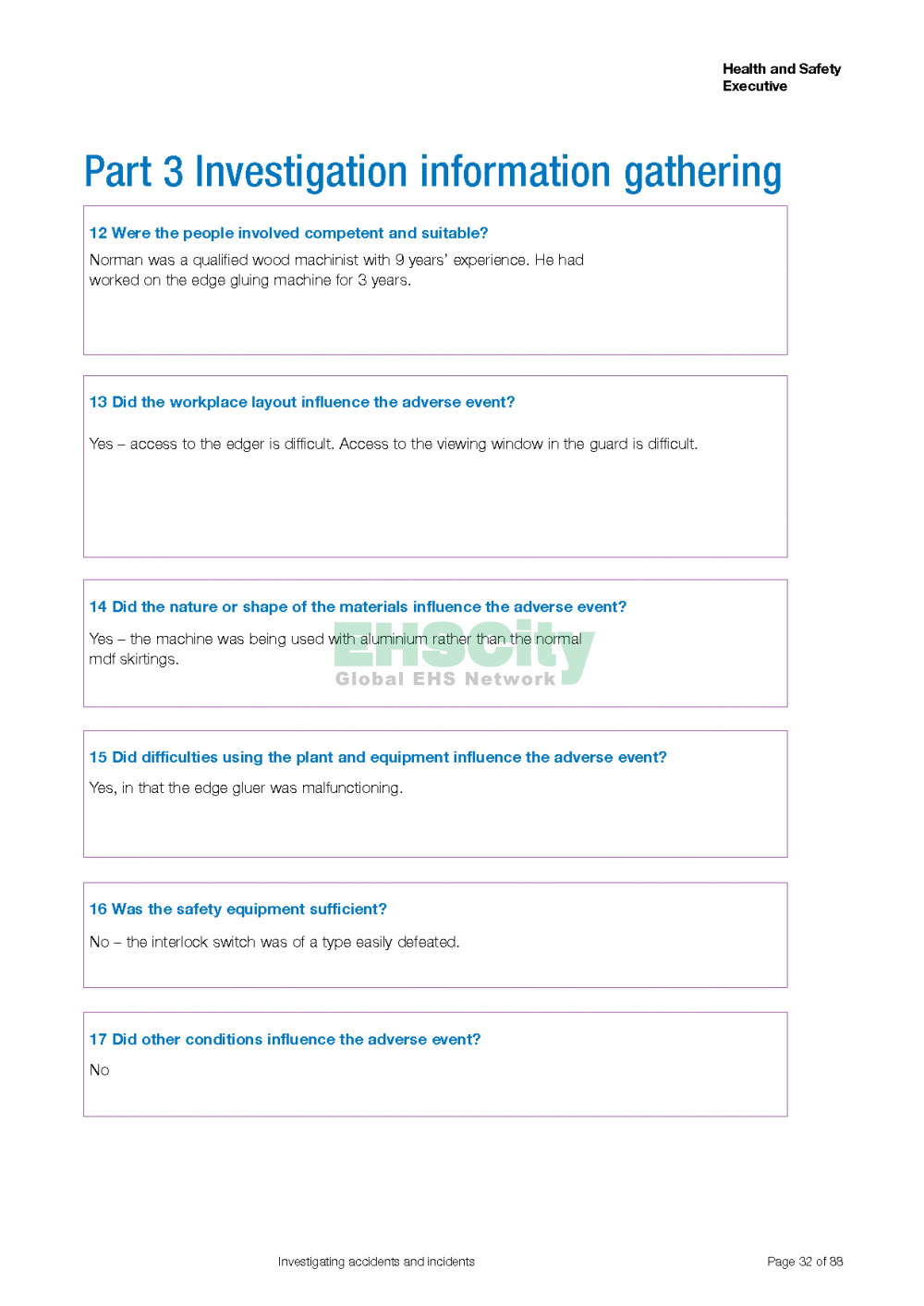

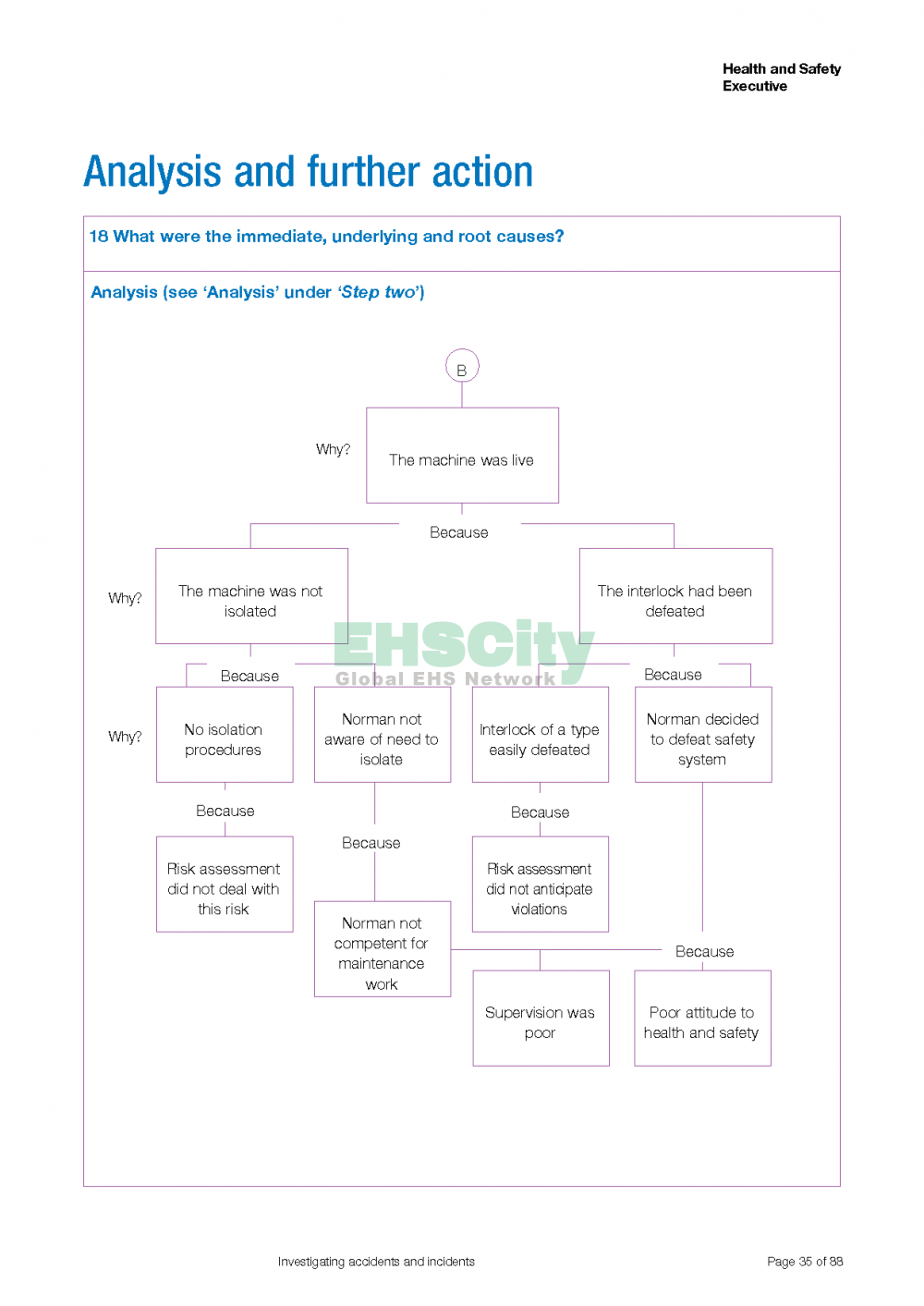

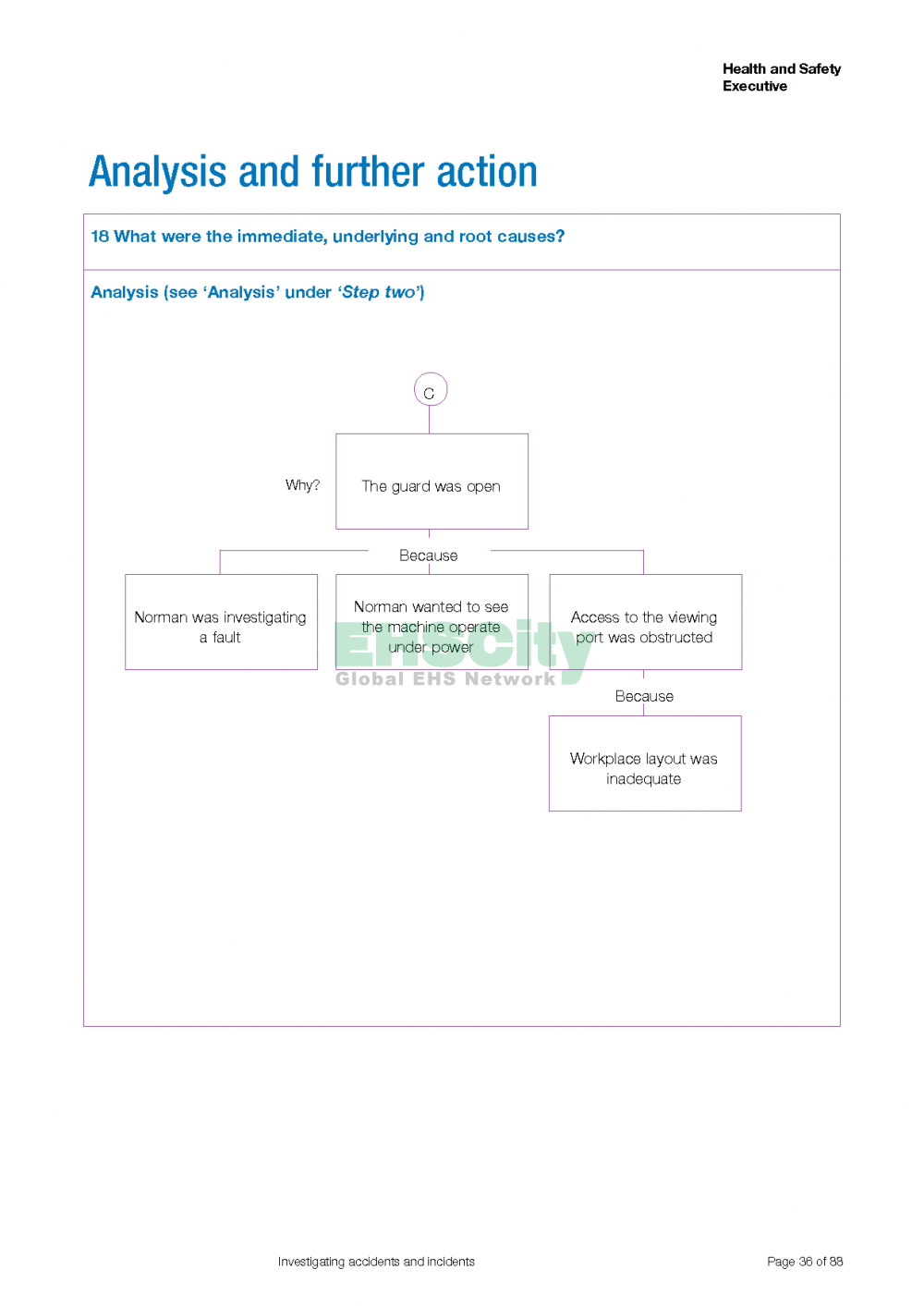

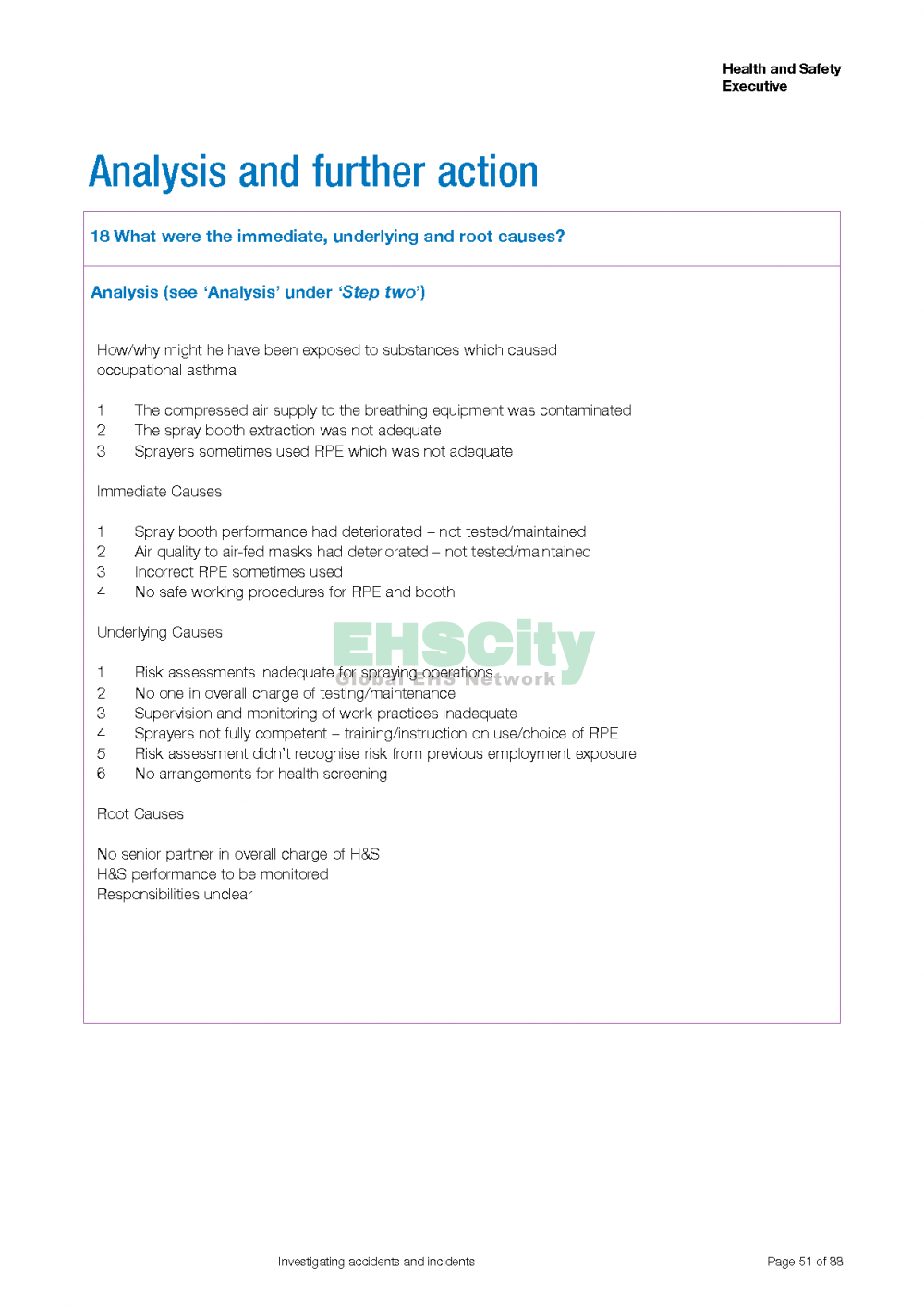

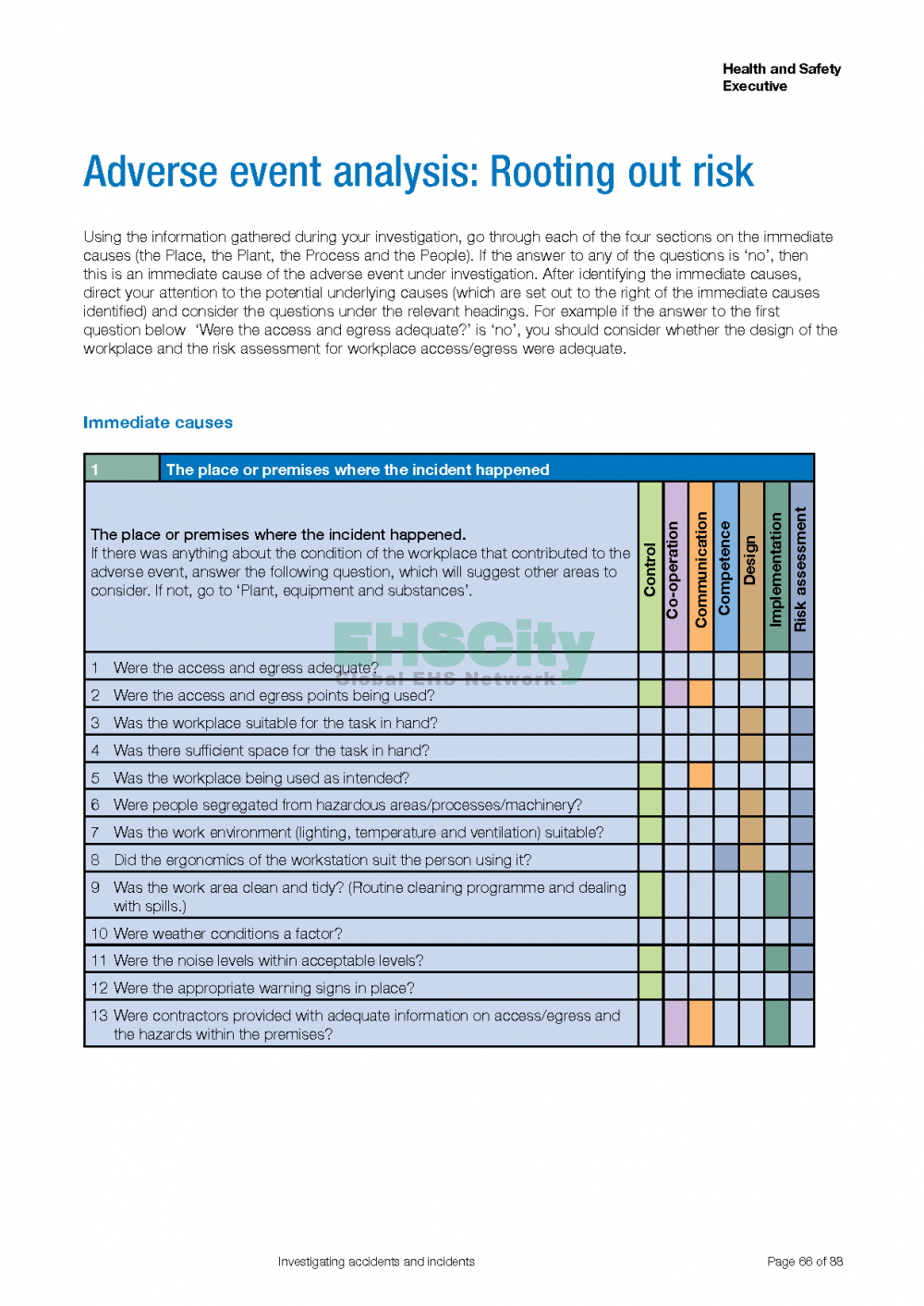

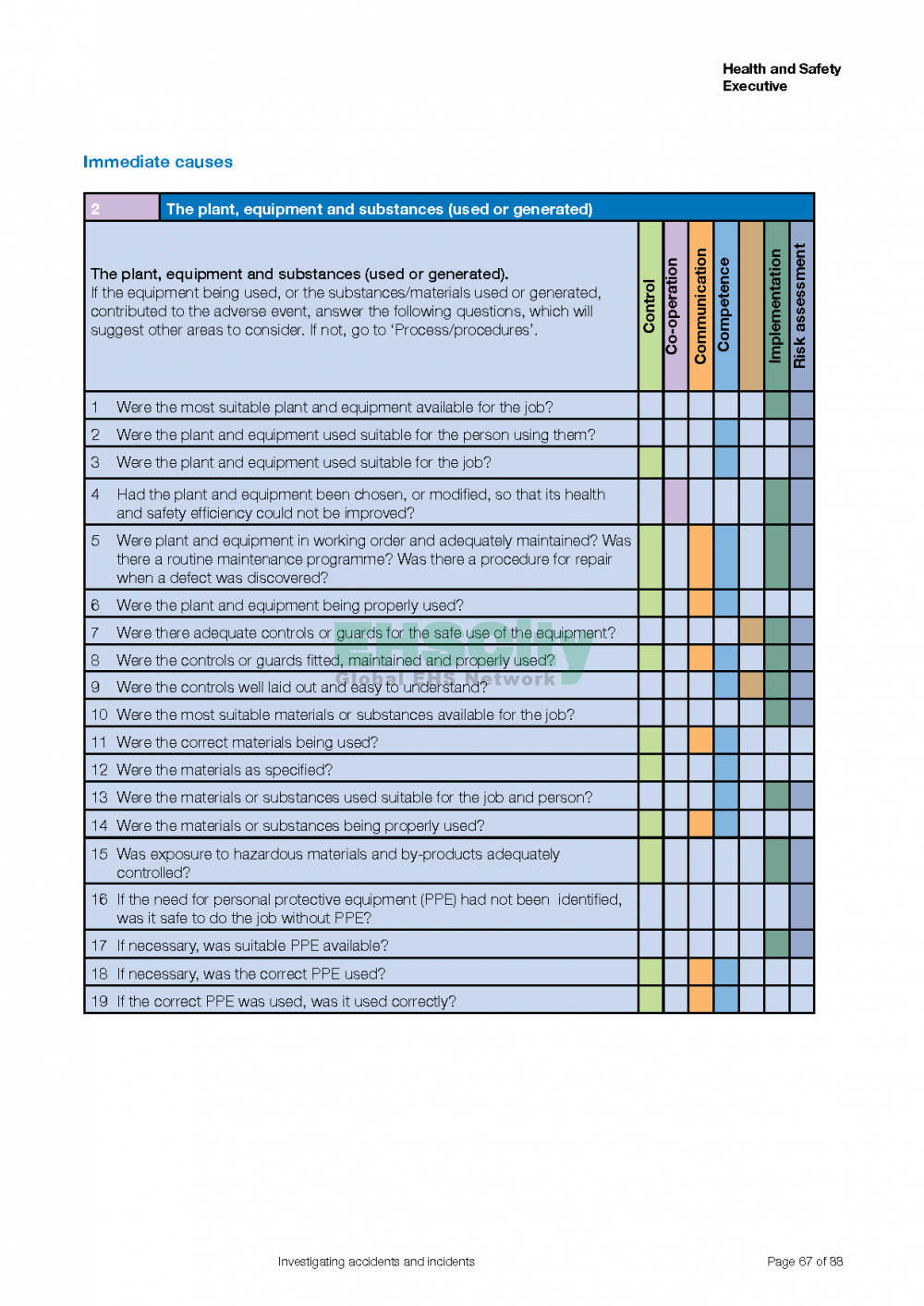

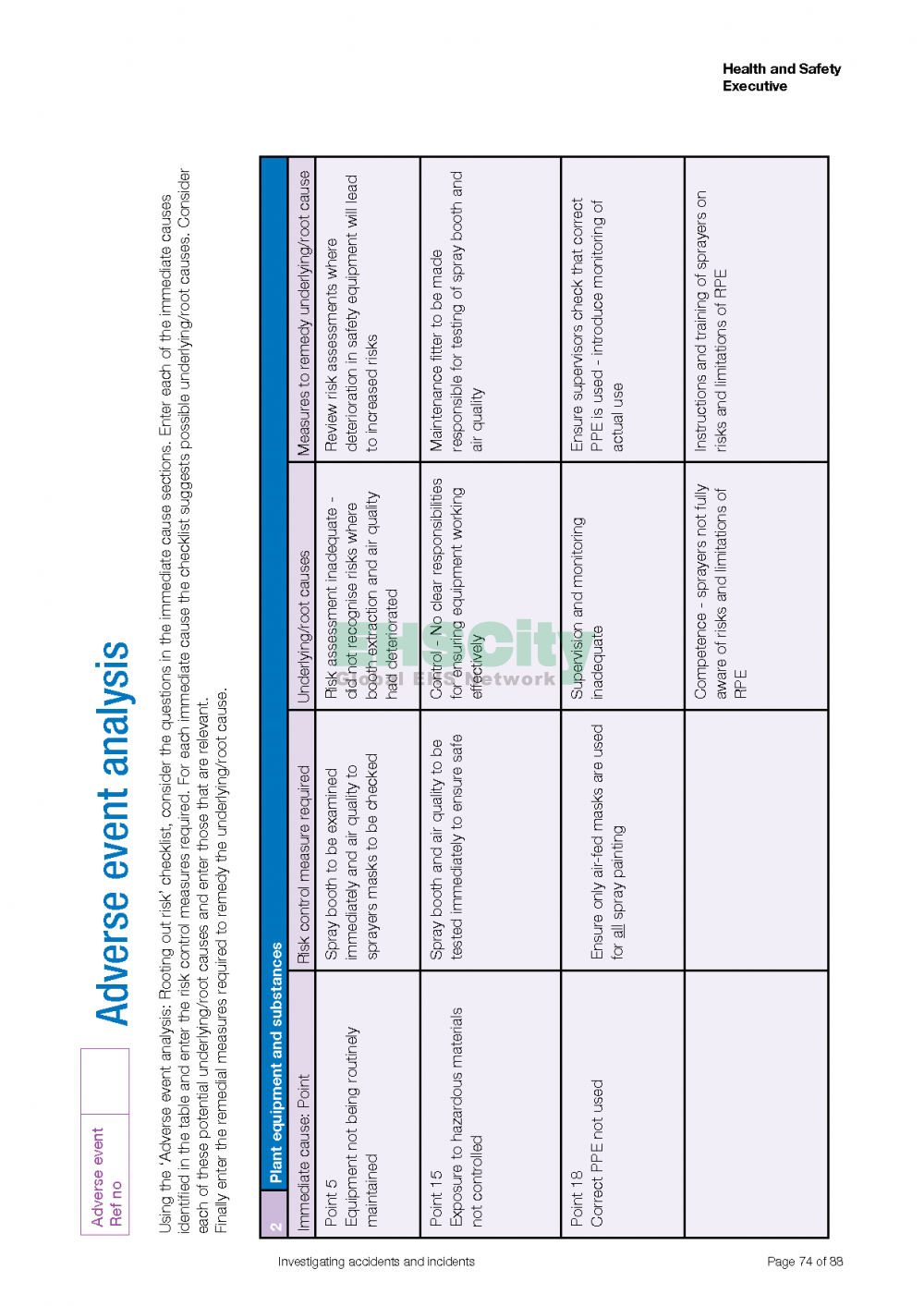

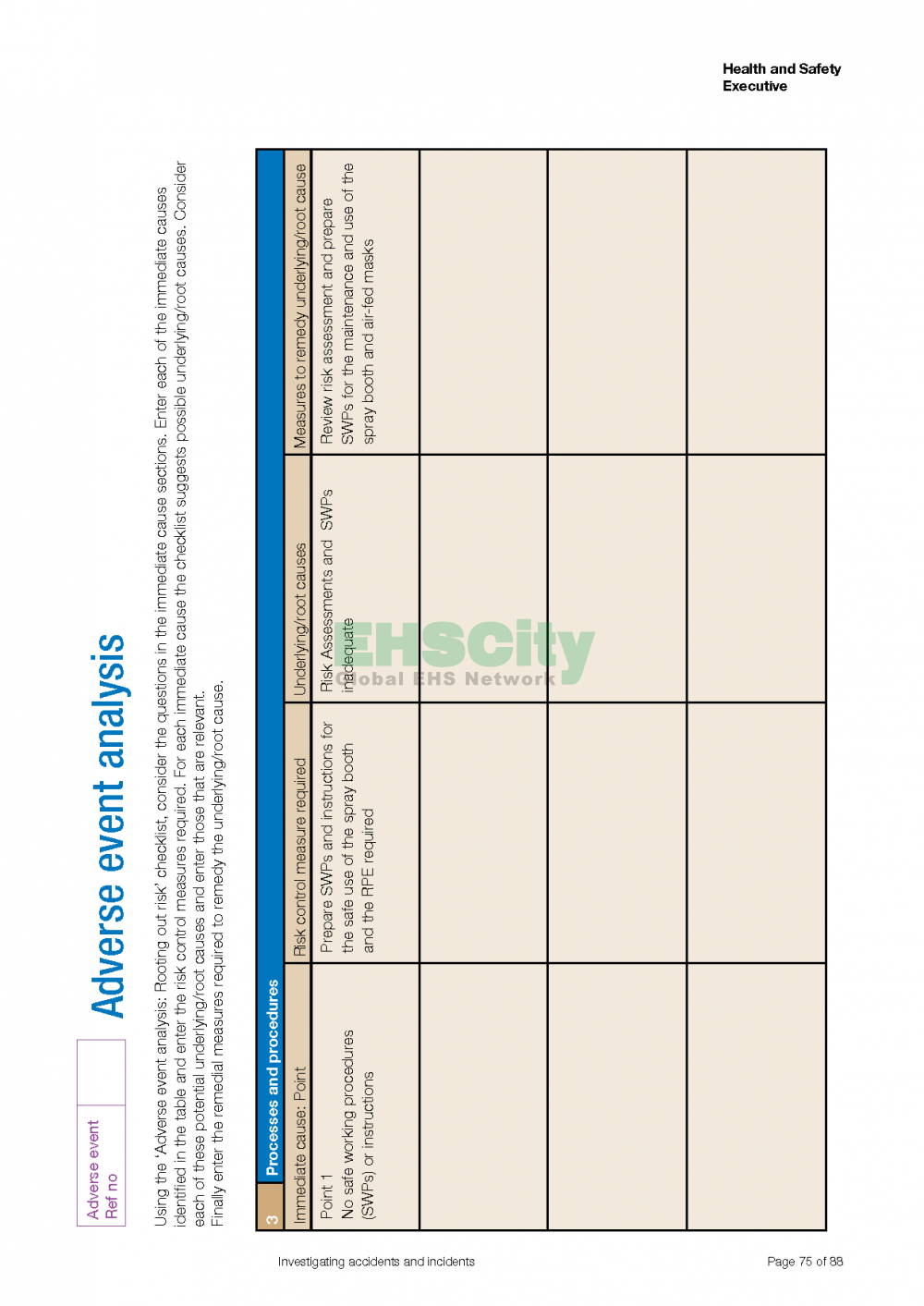

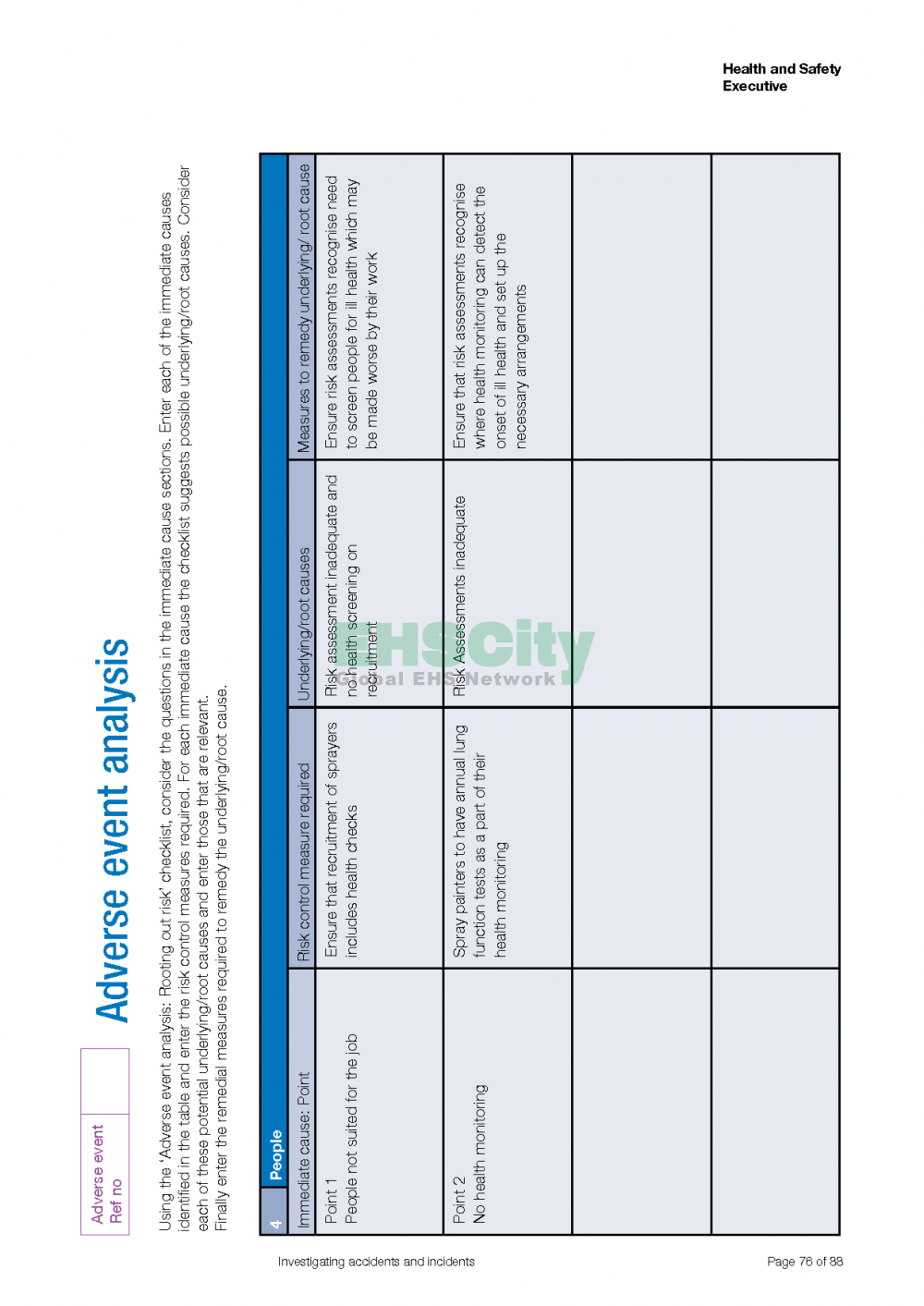

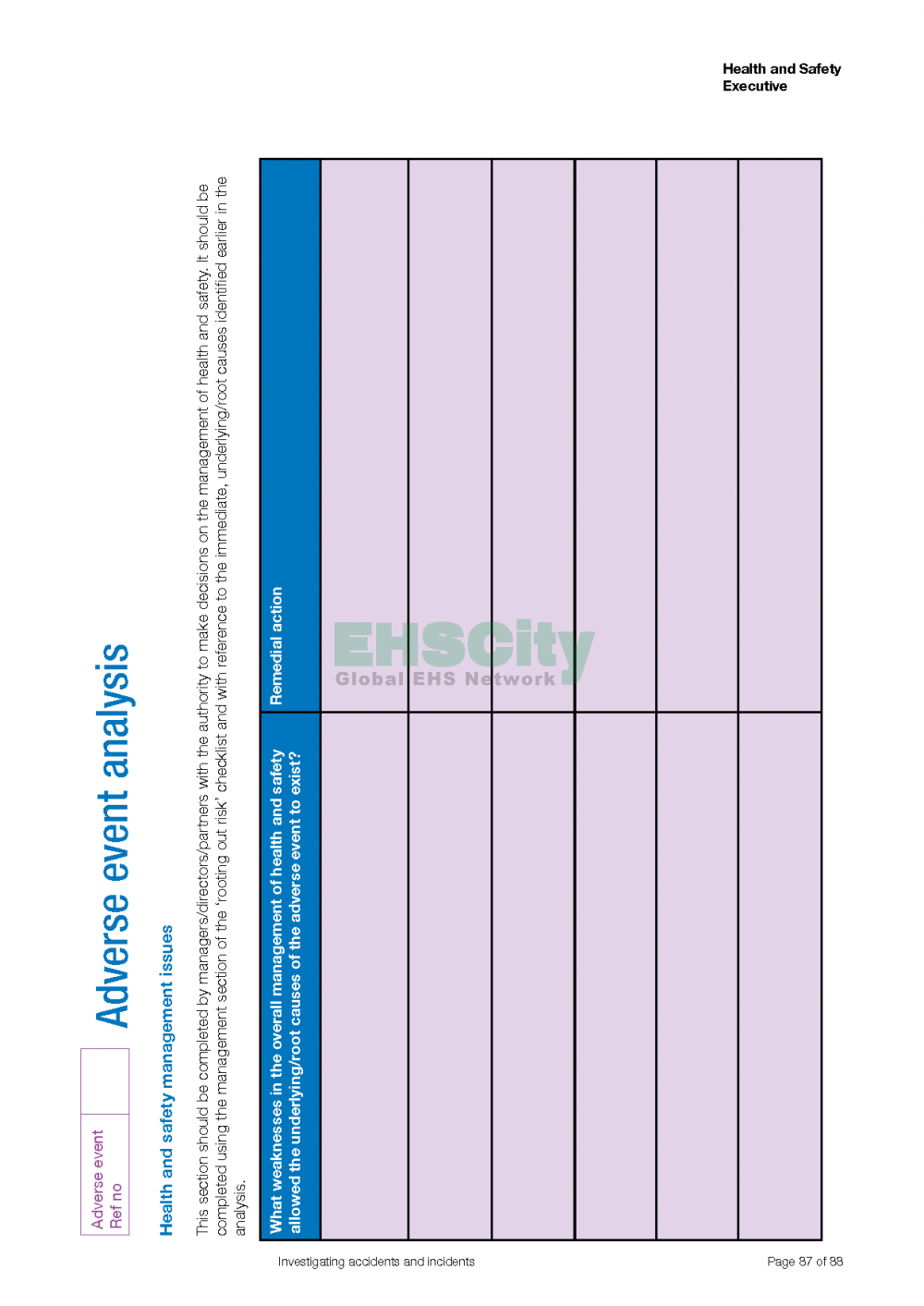

Fundamental to this process is the identification of basic, as well as immediate, causes. To facilitate this, the five components of this Loss Causation Model can be very helpful:

1. Losses: In this column, the investigator lists all losses.

2. Incidents: Here the investigator specifies the physical events, e.g., "Lisa was struck by a load from a moving forklift."

3. Immediate Causes: based on the collected evidence, the supervisor lists the substandard acts and substandard conditions that preceded Lisa being struck. Example: Failure to warn: The forklift shift driver and the mechanic failed to warn about the faulty brakes.

4. Basic or Root Causes: These are the underlying reasons why the immediate causes existed. Here are the root causes for the failure to warn:

- Mental stress: Working double shifts, the mechanic had more work than he could handle.

- Lack of skill: The forklift driver did not have adequate training.

- Inadequate motivation: The priority of things to be done was confusing to the mechanic because he had so much to do.

- Inadequate leadership: Unclear relationships in reporting and conflict in work planning with regard to the mechanic.

- Inadequate work standards: The forklift should have been tagged as out of service for repair but it was not.

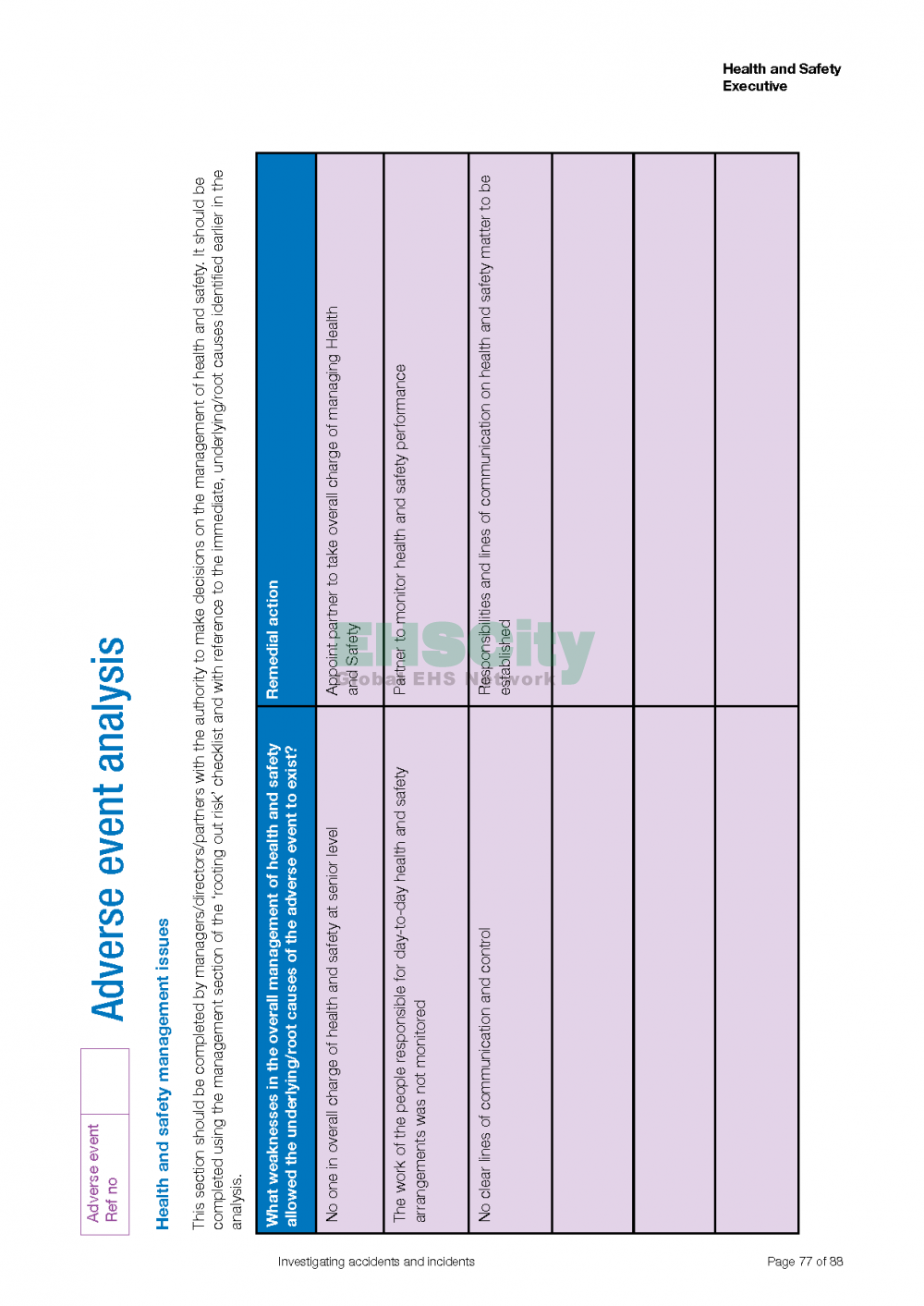

5. Lack of Control: These basic causes should then be taken a step further to analyze the organization's overall loss control program, program standards and level of compliance with those standards to determine the underlying reasons why those basic causes exist.

This level of analysis is a management function. There are 20 elements in a loss control system. These include such factors as Leadership and Administration, Planned Inspections & Maintenance, and Critical Task Analysis and Procedures.

After the analysis is completed, the next task is to develop remedial actions. These are either temporary, permanent or both:

Temporary: These actions address immediate causes, e.g. take the forklift out of service and repair it.

Permanent: These address permanent causes, e.g., develop a system to purchase better seals, revise procedures, revise the training program for future quarterly sessions.

Both: Conduct audits to make sure training is effective.

After the causal analysis and development of remedial actions, the investigator puts the investigation together in a brief summary for the next higher level of management.

By following the three-phase process described here, organizations can reduce losses to people, property, process and the environment. The amount of savings can be considerable.

BIO: Allan T. Goldberg is senior consultant for Det Norske Veritas (U.S.A.), Loss Control Management, creator of Practical Accident Investigation Series, an interactive video training program. Additional information on accident investigation and loss control management is available from DNV Loss Control Management at 800-486-4524 or at 4546 Atlanta Highway, Loganville, Ga. 30249.

Occupational Hazards, November 1996, page 33